This is Blog No 91

The Prime Minister is making it very clear that he is determined to build the energy infrastructure he thinks we need. Tightening up the rules for judicial reviews will help, he says. But in reality, his big problem is securing better consent for unpopular projects.

Although the Labour Manifesto was explicit about the expansion of renewable energy sources, and creating the public-owned GB Energy, it was a bit vague about ‘community benefits’.

Yet many people think that the path to a green economy is tricky and that, without some forms of palliative sweeteners, resistance to change will slow down or negate the progress.

They are controversial. Not because community benefit payments or projects are wrong in principle, but because they can be viewed as a ‘bribe’ to stifle objections. This is not surprising, as they are voluntary. Critics of major energy projects allege that community benefits only appear on the agenda when project promoters are in trouble or face significant opposition. This is why there is growing consensus that they should be mandatory; all major projects should provide community benefits. It is not current Government policy … but watch this space.

So, what difference might they make to consultations? Will consultees want to focus on the promised benefits, and will they detract from the fundamental debate of whether or not to proceed with the project? Or would knowing how a development might lead to local improvements be helpful in ensuring that consultees take the broadest possible view of the proposal? Should there, perhaps be a separate consultation just on the ‘community benefits’?

Initially, however, we MUST have some standards for community benefits, if only to establish their credibility.

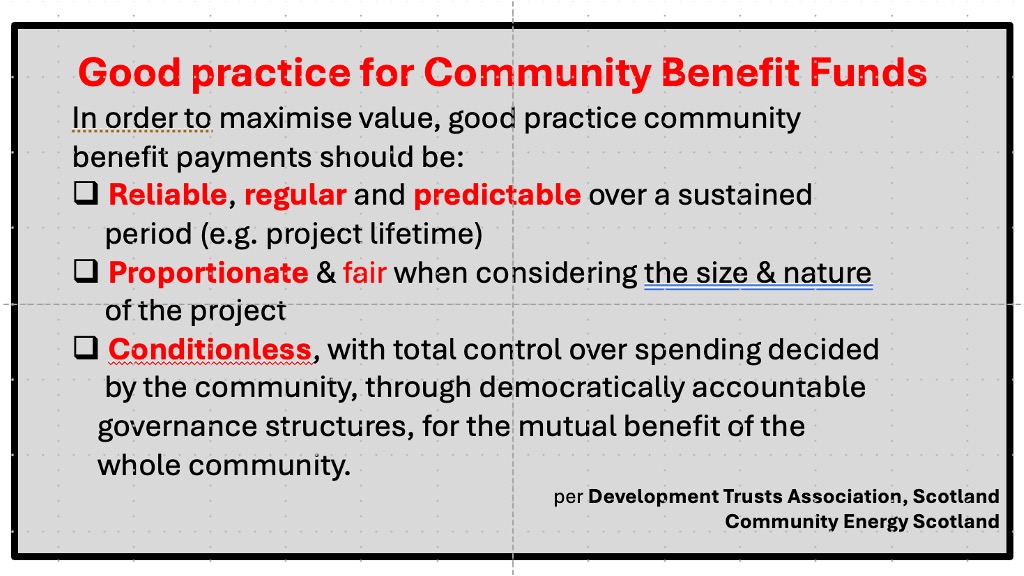

Notable in the recent debate has been an excellent paper from the Scottish Development Trusts Association and Community Energy Scotland. Their simple proposal is shown in the panel and may help restore faith in the principle.

Without adherence to such requirements we will continue to have the kind of concerns expressed in a Westminster Hall parliamentary debate on 24th October. One MP complained that in her constituency, it was a case of “large developers offering tokenistic gestures and small sums of money”. For onshore wind projects, the Scottish proposals go as far as to suggest specific figures that amount to a minimum of 2.5% of the generated revenue. Clear commitments of this kind would enable developers to factor these sums into their calculations from the outset – rather than reluctantly absorb them by reducing their profits after the event. The other advantage is that consultees could have more confidence in proposals that are subject to consultation.

An important element in the proposed Scottish standard is the insistence on ‘democratically accountable structures.’ By this, they do not just mean handing over the money to a local authority. To quote their paper:

It should also be mandatory for developers to meaningfully engage with the community about the benefit

arrangement, and developers must be required to allow communities to have control over how the benefit payments

are spent…. the “fundamental principle” is that these funds belong to local people and therefore it is for local people

to decide how those resources are allocated.

Might this be the perfect application of participatory budgeting?

The underlying idea that seems to motivate Government Ministers is to compensate what they call ‘host’ communities for inconveniences and disadvantages they might suffer as we transition to a greener economy. Let’s recognise how novel a principle this really is.

I grew up in a small town in South Wales which was dominated by the Carmarthen Bay coal-burning power-station. No-one offered to compensate the local community whose sandy beach was sacrificed and who ingested the fumes when the wind was on the wrong direction. We were just grateful for the jobs it offered.

Today, people are more conscious of their health, their environment, and their rights, and are far less willing to sacrifice personal interests for the general good; this makes it more difficult to impose unpopular infrastructure upon communities.

These include airport runways – suddenly back in the news, solar farms, wind farms and the transmission grid projects needed to connect them. Lots of people will be affected.

The guiding principle is becoming known as JUST TRANSITION which seeks to protect those most affected by the inevitable change in technology and behaviours. Scotland has its own Just Transition Commission, and maybe we need something similar south of the border. The original emphasis was on avoiding unemployment when the sunset industries declined and driving forward the urgency of skills retraining. But today, the scope is much wider and policy-makers have to work with campaigners anxious about the loss of amenity, landscape values and the impact on house-prices. Pylons are an obvious case in point.

So, in all this, what is the role of consultation?

First, we have to engage more people in deciding upon the policies to adopt. Gone – or going fast - are the days when politicians can include far-reaching commitments in a manifesto and then rely on their parliamentary majority to force them through. Just look at the summersaults both the Sunak and Starmer governments have had to make over the Electric vehicle mandates hurriedly committed to a few years ago. Witness also the confusion over onshore wind turbines, or the High-Speed Two debacle. Consultations over national policies have to be far better.

Secondly, mitigation options for important proposals must be consulted upon. We still have developers whose attitude is to see how much support they can garner for their proposals and only offer ‘concessions’ when they think the opposition is becoming a real threat. Given it may be impossible to avoid affecting some people badly, mitigation must be designed into proposals right from the start. Despite the media distortions of the recent story about HS2’s design of a £100m structure to protect Bechstein bats, it led to a widespread view that wildlife was being treated better than people. The only remedy is to engage and consult stakeholders early enough to help secure the least damaging proposals.

Third, decision-makers must be better identifiable and accountable. As we enter the age of AI-supported consultations, communities may start to fear that whatever they say, their views will only be considered by a computer and that it will be pre-programmed to support the consultor’s proposal! Important safeguards are needed here, and one of them is to ensure that the human dimension of decision-making is preserved and made visible. I anticipate a resurgence of person-to-person dialogues and public events that will have to be far more meaningful than of late.

In summary, ‘community benefits’ will certainly feature in the changing landscape of policy-making, and it is essential that they are influenced by extensive, well-informed and inclusive public engagement and consultation.

Rhion H Jones LL.B

For more like this, and to receive the monthly Consultation Catch-up, click here

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.