Draft Blog 87

A High Court ruling in R (Wallis) v North Northamptonshire Council suggests that the failure to consult cannot be challenged unless you find out pretty quickly. For those who remember Donald Rumsfeld as US Defence Secretary, the situation will remind them of the spectre of ‘unknown unknowns’

In this case residents in Corby have been told by the Judge that they should have sought legal redress earlier.

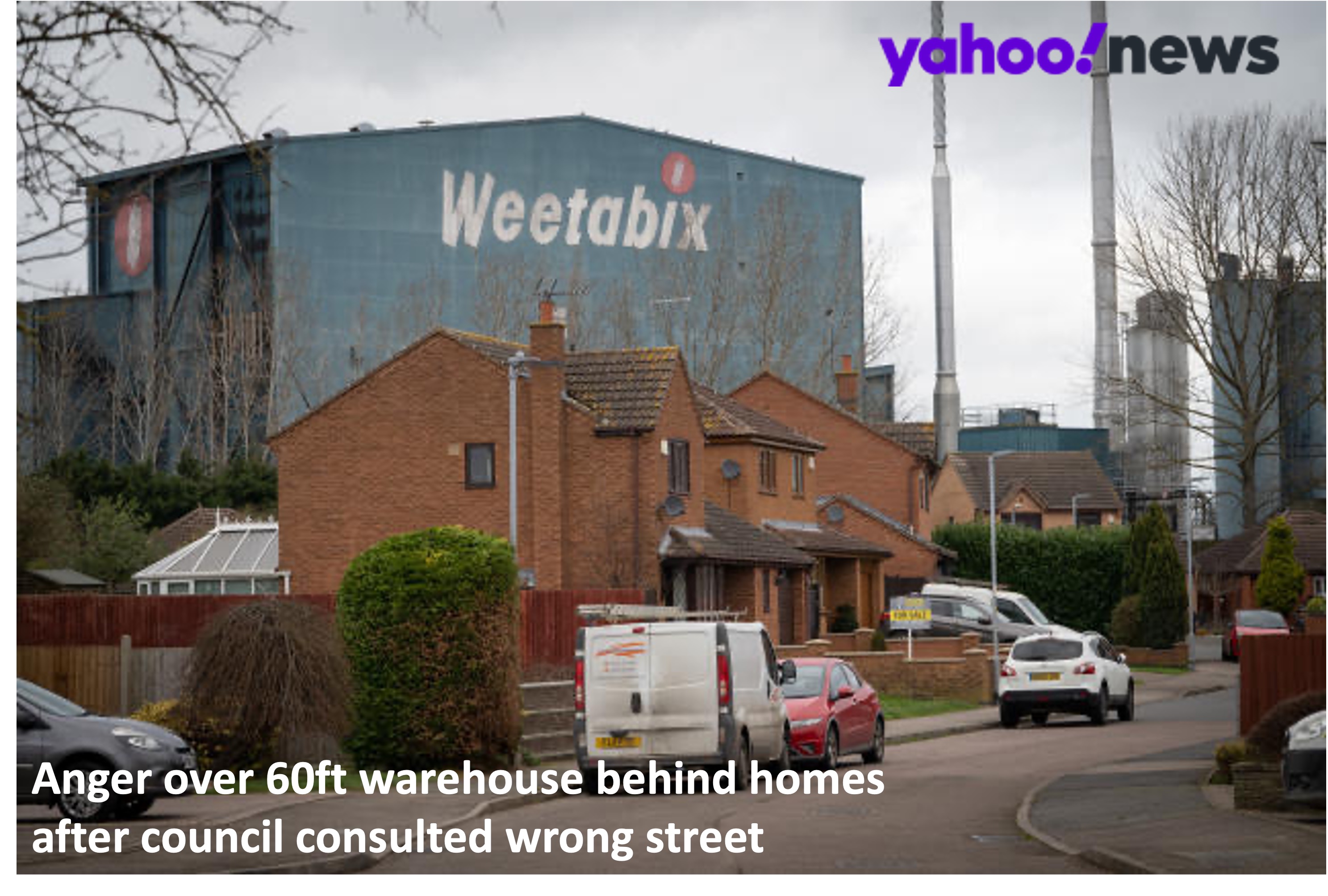

This is the tale of two Weetabix factories which were closed. The Council gave planning permission for the erection of a warehouse but sent consultation letters to the wrong addresses because it confused the two sites. When Mrs Wallis and her neighbours realised what was happening, they approached the planning department, and the Council discovered its error. It asked the developer to halt construction but building continued. Other attempts to solve the problem took place; radio and television reporting highlighted the ‘egregious’ mistake made by the Council. Eventually they approached lawyers and a claim for judicial review was lodged.

There are good public policy reasons why Courts are reluctant to interfere with administrative decisions taken by public bodies. Planning is a particular case in point – as developers who have been granted planning permission must obviously be allowed to build according to the terms of the consent. Legal uncertainty could cost them huge sums. The rule is that a judicial review must be sought within six weeks, or at least within 3 months. Very few exceptions are allowed.

In this case, despite the Council arguing that because it had arranged a site notice and that the planning permission was therefore lawful, everyone seems to accept that a horrible mistake had been made. Until September 2024, residents insist that they thought the demolished factory was likely to be replaced by housing. When they saw a much bigger building being erected, they pursued a range of solutions but did not seek legal redress. The Judge thought they waited too long. She helpfully suggests that residents may have recourse to the Local Government Ombudsman but a resulting wrap over the knuckles is unlikely to inconvenience either the Council or the developers.

The case throws up several issues that may trouble those involved in public engagement and consultation:

- The most obvious point is how on earth could such a mistake happen? How could professional planners not notice that a consultation asking for views on such a project yielded no relevant responses? As it went to the wrong street, chasing up on a ‘nil return’ should have revealed the error. Or is it that in some places consultation is regarded as a mechanical tick-box exercise with officials prone to regard it as ‘job done’ once the letters of invitation are sent? In this case, I am as concerned with the attitude of the Council to the consultation they DID undertake as with the plight of those who were mistakenly omitted, and the consultation that DID NOT happen!

- Cases like this often turn on the specific facts, and the Council relied on notices in newspapers or lampposts and advertisement hoardings at disputed locations to show that residents should have sought advice as to what was happening. All part of a culture focused on inputs rather than outcomes. Whose job was it to ensure that local residents were aware and as comfortable as possible about what was due to happen to them? Where were the ‘checks and balances’ provided by involving elected members? When they eventually became involved, the time taken to engage them contributed to the residents being ruled to have been ‘out of time’.

- The lack of a legal remedy in a case like this will strike many as being unjust. They will question whether Courts are as sensitive to life-changing issues for unsuspecting families as they are to the interests of developers and bureaucrats. One can see the Judge’s dilemma. If she quashed the planning permission, and if, for example, an additional unit for an oversupplied warehouse market was pulled down to provided more desperately needed houses, the Council would have to pay damages to the developer.

- Maybe the answer is to toughen up the law by making everyone realise the one thing public bodies cannot do is to skimp on their consultation obligations. Getting away with ‘egregious’ mistakes sets an appalling example – as does going to Court and trying – unsuccessfully as it happened – to persuade the Judge that they had consulted adequately when they manifestly hadn’t. Perhaps in cases like this it should be public policy that when consultation is shown to have been inadequately done, a compulsory period of conciliation and arbitration should be necessary, with the time taken for this to be omitted from the calculation of eligibility to mount a legal challenge?

- If this case goes to appeal, I trust that residents will argue that the Council should also have acted faster than it did, revoked the planning permission (which it could still do!) and done more to prevent residents from losing their common law right to judicial review by its tardy response. Can they argue that, once it realised its mistake, residents had a legitimate expectation that the Council would revoke the permission – rather than maintain the status quo and deny liability for its actions?

It’s a sad tale with a bitter ending, but it reinforces yet again the need for public bodies to take their consultation and engagement responsibilities seriously. Not an inconvenient element of process that stands in the way of achieving targets or political goals.

For consultees or potential consultees, there is an urgent need to make people more aware of their rights. Campaigning organisations, community groups and special interest specialists everywhere need to know when they can expect to be consulted, and the high standards which need to be met, if the exercise is to be meaningful. By 12th December, the Government wants to know what we all think of their framework for a new Civil Society Covenant. I suggest we all lobby to strengthen it by ensuring far better safeguards to protect those who are not consulted properly … in the hope that the injustice that followed the closure of a Corby Weetabix factory never happens again.

Rhion H Jones LL.B

Commentaries are prepared primarily to help consultation practitioners take account of developments in the law and to guide them on situations where legal advice should be sought. They are no substitute for reading Court judgments or studying statutory provisions or associated Guidance.

Booking link is HERE

Rhion has monitored and written commentaries on the Law of Consultation since 2007 but does not provide legal advice. He will, however, be happy to discuss the content of this or any other commentary.

See Rhion's Speeches etc - click here

For More like this - free of charge: now click here

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.