This is Blog No 77

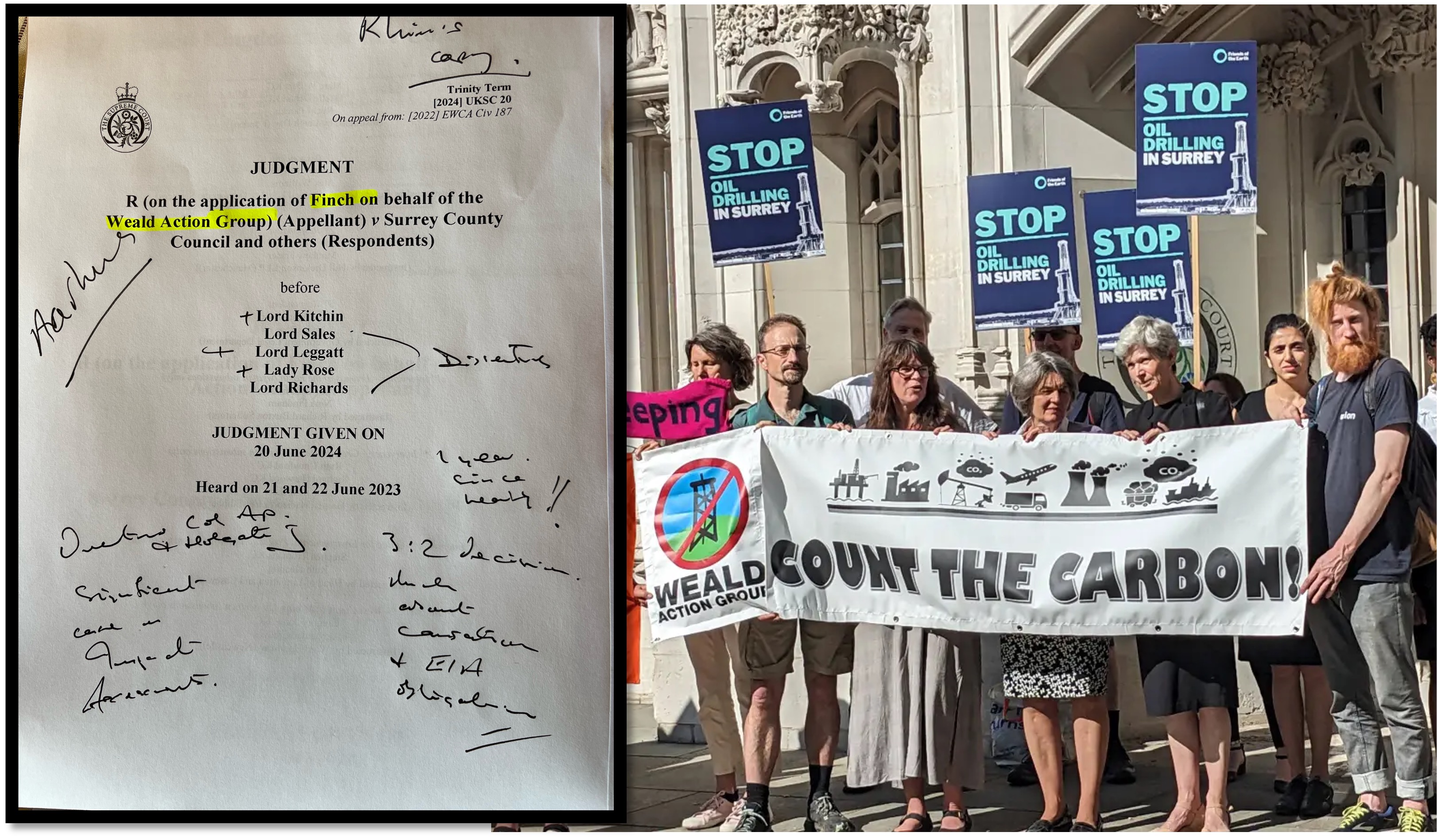

I have now had the opportunity to look closely at the Supreme Court decision that hit the headlines just before the General Election. In Finch v Surrey County Council [2024] UKSC 20, by a majority of 3 to 2, Law Lords decided that Surrey had acted unlawfully to grant planning permission to retain and extend the extraction of oil at Horse Hill, Surrey. This is because the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), whilst examining the direct impact of the project, had failed to identify the indirect consequences when that oil was used downstream.

Lawyers have had a field day.

The case first went to the High Court where the Weald Action Group failed to persuade the Judge. It then went to the Court of Appeal, where it was also unsuccessful, albeit on subtly different grounds. The Supreme Court heard it in June 2023, and a full year later, we now have two comprehensive and erudite judgments contradicting each other, with Lord Leggatt (plus two colleagues) explaining why Surrey CC was wrong, and Lord Sales (plus one) finding for the Council. Both are well-argued, authoritative and compelling!

To the winner, the spoils. Climate campaigners are, understandably cock-a-hoop. Here is final proof that our political institutions have been too cautious and have hidden behind a narrow interpretation of EU and national laws designed to steer us towards using less carbon. If planning authorities were obliged to consider the long-term, downstream effects of their policies, surely, they argue, we would all think twice before approving initiatives that jeopardise our targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

But others are less sure. Of course, the oil and gas lobby will emit their anger. But hard-pressed local authorities will choke on the unintended consequences. And Government Ministers may worry about a continuous stream of legal challenges delaying their plans for economic growth. Those of us who would like to see clarity in the law merely put our heads in our hands and despair.

For the truth is that, in practice, this should be a really meaningful step forward. If we go back to first principles, the main purposes of securing an authoritative view of the likely impacts are to assist decision-makers to make more informed choices - but also to facilitate public debate and discussion. The rationale was very clearly stated 21 years ago by Lord Hoffman:

“The directly enforceable right of the citizen which is accorded by the [EIA] Directive is not merely a right to a fully

informed decision on the substantive issue. It must have been adopted on an appropriate basis and that requires

the inclusive and democratic procedure prescribed by the Directive in which the public, however misguided or

wrongheaded its views may be, is given an opportunity to express its opinion on the environmental issues.”

(Berkeley v Sec of State for the Environment 2001)

The question is to what lengths should developers and applicants go in researching and publishing their views of the impacts. The argument of Lord Sales’ dissenting judgment in this case was that this went beyond what a local planning authority needed to consider.

“It would clearly impose disproportionate costs and burdens on both developers and national authorities

if information about all downstream or scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions had to be gathered and

presented by developers and had to be assessed by planning authorities (in particular, at the local level)

in circumstances where such information could not inform in any helpful or appropriate way the

decisions to be taken by those authorities.”

He also has concerns about which ‘public’ need to be consulted. He points out that the thrust of the Aarhus convention’s ‘pillars’ – upon which the whole edifice of EIAs is constructed - is about the participation of ‘the public concerned’, defined as those having an interest in the environmental effects of a project “by virtue … of their nature, size or location”.

Lord Leggatt will have none of this, preferring instead a clear-cut ruling to the effect that “…there was no basis on which the council could reasonably decide that it was unnecessary to assess the combustion emissions”

For planning lawyers, and environmental campaigners, there are continuing questions about ‘causation’ and the ‘likely’ effects of various projects. For an excellent YouTube discussion of these by Keeting Chambers and Pinsent Masons, see here.

But for those of us primarily concerned with public consultations on important decisions like this, what are the implications? I advance four quick observations.

- The critical importance of Impact Assessments

They are not the be-all-and-end-all of Gunning Two, and the requirement to enable consultees to give ‘intelligent consideration’, but they are a key part of the explanation provided in a consultation. If they do not provide sufficient detail of the foreseeable results of what is proposed, be prepared to have the consultation declared unlawful. Assume also that if you are offering several options, the differing impacts have to be specified. They must not be a nominal, tick-in-the-box process, but shown to be based upon solid, specified research, easily accessed by consultees – not tucked away in obscure corners of websites or document sets.

- The challenge of communicating technical issues

The danger is that EIAs become voluminous, jargon-infested analyses incomprehensible to laypersons and the general public. I remember upsetting good friends in TfL by commenting that the EIA for the contentious London ULEZ extension consultation was only meaningful to someone with a PhD in transport modelling. Maybe that was a little harsh, but the complexities of some subjects make it difficult to present the evidence in a simple way. For example, my experience of consultation documents prepared for airspace change – full of detailed maps with noise contours, factored by flight frequencies etc left me scratching my head and wondering how others managed to interpret this data. Here is the challenge for communications professionals – to devise ways to present this data for the different audiences that may wish to participate. Great scope for talented consultancies with imaginative ideas.

- A duty to explain and engage

This is why it cannot be sufficient just to ‘publish and be damned’. In the Politics of Consultation (2018), Elizabeth Gammell and I sought to promote three important duties for consultors (at pp 271-290). They are to define, to explain and to engage. Whilst legal argument in the Finch case focused on what the EIA should say, the more practical question would be what difference might it make to those who read it! In 2007, Frank Luntz, a US pollster wrote a best-selling management book whose title included the phrase “It’s Not What You Say. It’s What People Hear.” Applying this to EIAs full of technicalities, there is that challenge of communications, but also an obligation for those who want the public to consider the issue – to reach out at scale– to have an effective dialogue in person if necessary. Posting something on a website is not enough.

- The bigger picture

Finally, this case illustrates the difficulty of providing the right focus for public dialogue. By instituting National Policy Statements (NPSs), the 2008 Planning Act tried to separate the discussion on ‘what we build’ from ‘where we build it’ in an attempt to avoid every separate major project planning application from re-opening the wider questions. Climate change is the widest ‘big-picture’ issue of them all, and there are many who will worry that asking Councillors in Surrey to take decisions by reference to matters of national or international policy priorities may be – as the phrase goes ‘above their pay grades’.

However, in matters of public consultation, respondents have always offered their opinions on the bigger picture, and part of the skills-set for public engagement professionals is the know-how to analyse such data and manage these situations.

To conclude, the Supreme Court – and its failure to reach a unanimous decision – shows that there is still uncertainty as to the precise legal obligations of those wishing to promote projects and policies with troublesome consequences. But in terms of facilitating public dialogue and consultation, it there is absolute clarity that we need improved methods and more investment in the task of educating the public about the issues and securing its support for tough decisions at challenging times.

Rhion H Jones LL.B

Commentaries are prepared primarily to help consultation practitioners take account of developments in the law and to guide them on situations where legal advice should be sought. They are no substitute for reading Court judgments or studying statutory provisions or associated Guidance.

Rhion has monitored and written commentaries on the Law of Consultation since 2007 but does not provide legal advice. He will, however, be happy to discuss the content of this or any other commentary.

See Rhion's Speeches etc - click here

For More like this - free of charge: now click here

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.