This is Blog No 26

Failures by Ministers to analyse consultee submissions and publish a response lie at the heart of a dispute which has led to a legal challenge of a policy U-turn on plans for an independent appeal mechanism for Council decisions on social care.

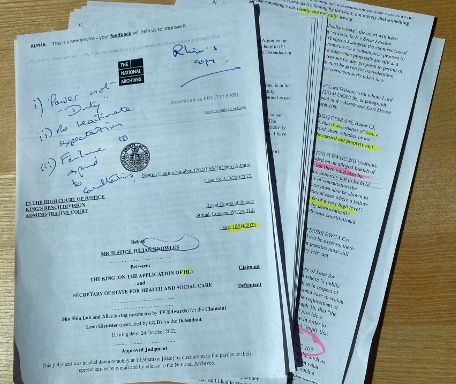

I have been studying the judgment of Mr Justice Knowles in R (HL) v Secretary of State for Health and Social Care [2023] EWHC 866 (Admin), as it illustrates the inadequacy both of the Government’s Consultation principles and the limitations of the Gunning Principles.

It arose because of the widespread view that decisions on social care taken by local authorities should be subject to an independent appeal. This was a claim that Ministers should have consulted before deciding to defer indefinitely a previous policy commitment to introduce such a mechanism.

Pressure had been mounting for some years before the Care Act 2014 was passed. In 2011, there had been a consultation by the Law Commission, and in 2013, another by the relevant Government department. Accordingly, when the Bill received Royal Assent, S.72 gave the Secretary of State the power to create Regulations to establish such an independent appeals process. David Cameron’s Government seemed committed to introducing them, and in 2015, consulted upon them.

In the years that followed, however, Government priorities under the May and Johnson administrations changed, and policy towards social care became a very contentious issue. Appeals against social care decisions, it now appeared, would have to wait until the wider policy on social care became settled. As is well known, this never happened, and it has been in a state of flux ever since!

In this case, a severely disabled person had a distressing and unsatisfactory experience attempting to challenge a ‘care package’ delivered by an unnamed County Council. Uncontested evidence supported an argument that relying on internal processes can leave individuals without recourse to an independent remedy – the very reasons that had led to Government acceptance of the principle of appeals in the first place. The claimant argued that the change in policy should have been subject to public consultation, and this raised important issues concerning when there needs to be such an exercise. And when none is needed.

The Act did not require Ministers to enact Regulations on appeals – it merely permitted them. It was a ‘power’ - not a ‘duty’. The key question was whether it was lawful to defer doing so without consultation. This was always going to be an ambitious argument as the claimant had to rely upon the view of Judges in the Richard III case (also in 2014) that a duty to consult may arise at common law where there had been an established practice of consultation. It would have created a legitimate expectation that any significant decision on such matters could not be lawfully taken without a consultation.

Judge Knowles rejected this, stating that, on the facts, there was no evidence that the practice of consultation had been ‘so consistent as to imply, clearly, unambiguously and without relevant qualification that it will be followed in the future.’ To read his judgment, one can see immediately the long-established reluctance of Judges to intervene in political decision-making. Courts have given themselves flexibility where conspicuous unfairness arises from a failure to consult, but this was not one of them.

However, the main takeaway from this judgment may not be a narrow legal point. More significant, I believe is that it demonstrates our confusion about the role of public engagement and consultation in the policy-making process.

For what emerged in this case is that the outputs of neither the 2013 consultation nor the 2015 consultation were ever published! There was no published analysis nor a Government response. We can infer that the balance of the argument in 2013 must have influenced Ministers when the Bill was drafted, but there was no transparency as to the dialogue that led the Government to legislate by means of a ‘power’ rather than a ‘duty’. Similarly, no-one knows how consultees responded to the detailed questions posed in 2015, and the extent to which this enabled Ministers to defer the appeals process indefinitely.

In a remarkable admission by the Dept of Health & Social Care, the judgment notes that, in relation to the appeals, ‘there were mixed views in the responses to the consultation. There was an even split between those in favour, against and no response. Many representative groups were in favour of an appeal system, but other responses were not in favour and there were no consensus.’ (Par 76)

This, therefore, is the first public disclosure of what was said. To anyone with experience of consultation processes, the paragraph screams out for deeper analysis. Who was against? And why? How urgently is the system believed to be required? Who would benefit? To what extent? And much else. In other words, the very stuff of policy-making.

But consider this.

The rationale for consultation is for a transparent debate that can be seen to inform decision-making. Failure to publish a report on the relevant consultation – as occurred in this case twice (!) prevents us from knowing what the arguments may have been and forming a view on whether Ministers have been reasonable in adopting a course of action. No wonder the claimant felt that all the policy-making procrastination and U-turns were taking place behind closed doors whereas the Government had, by its own actions, placed the issues in the public domain and invited an open debate via a consultation.

For here is the nub of the problem. There is no duty to publish the outputs – or even the outcome of a consultation. It is part of the Consultation Institute’s Consultation Charter which I helped to draft in 2003. But that is basically best practice. It is not one of the Gunning Principles – though probably should be added. There is not even a requirement to analyse the data emerging from a consultation. All that is required on these well-established common law tests is to show that decision-makers have given the consultation conscientious consideration – something that is probably tricky to evidence if you haven’t analysed the responses in the first place.

The Government’s own Consultation Principles document is a little firmer – and states that reports should be published normally within 12 weeks. But the enforcement of these standards is an utter shambles, with Governments able to ignore best practice whenever it suits them. To have to wait until a witness statement in the High Court about what consultees might have said on an important issue seven years ago is a disgrace – as well as being disrespectful to those who responded.

We must end the practice of Governments marking their own homework. We need an independent regulator to ensure that Ministers who consult the public also provide feedback to the public. If the Care Act case failed to establish that previous practice warranted a further consultation before abandoning an established policy, at least it has highlighted such process failures as will inevitably invite challenge in the Courts.

The Government, we hear, would like to reduce the number of judicial reviews.

In the case of public consultations, better regulation might do the trick.

Rhion H Jones LL.B

Commentaries are prepared primarily to help consultation practitioners take account of developments in the law and to guide them on situations where legal advice should be sought. They are no substitute for reading Court judgments or studying statutory provisions or associated Guidance.

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.