This is Blog no 61

Who would wish to be a legislator these days?

You face relentless pressure to initiate or approve new laws to regulate anything and everything – mostly worthy causes and probably popular with the public at large.

It is particularly difficult in the wake of accidents or tragedies where everyone agrees that the State might be at fault for not having anticipated a threat, and where bereaved families, injured people and surrounding communities campaign for legislation. They naturally attract widespread support.

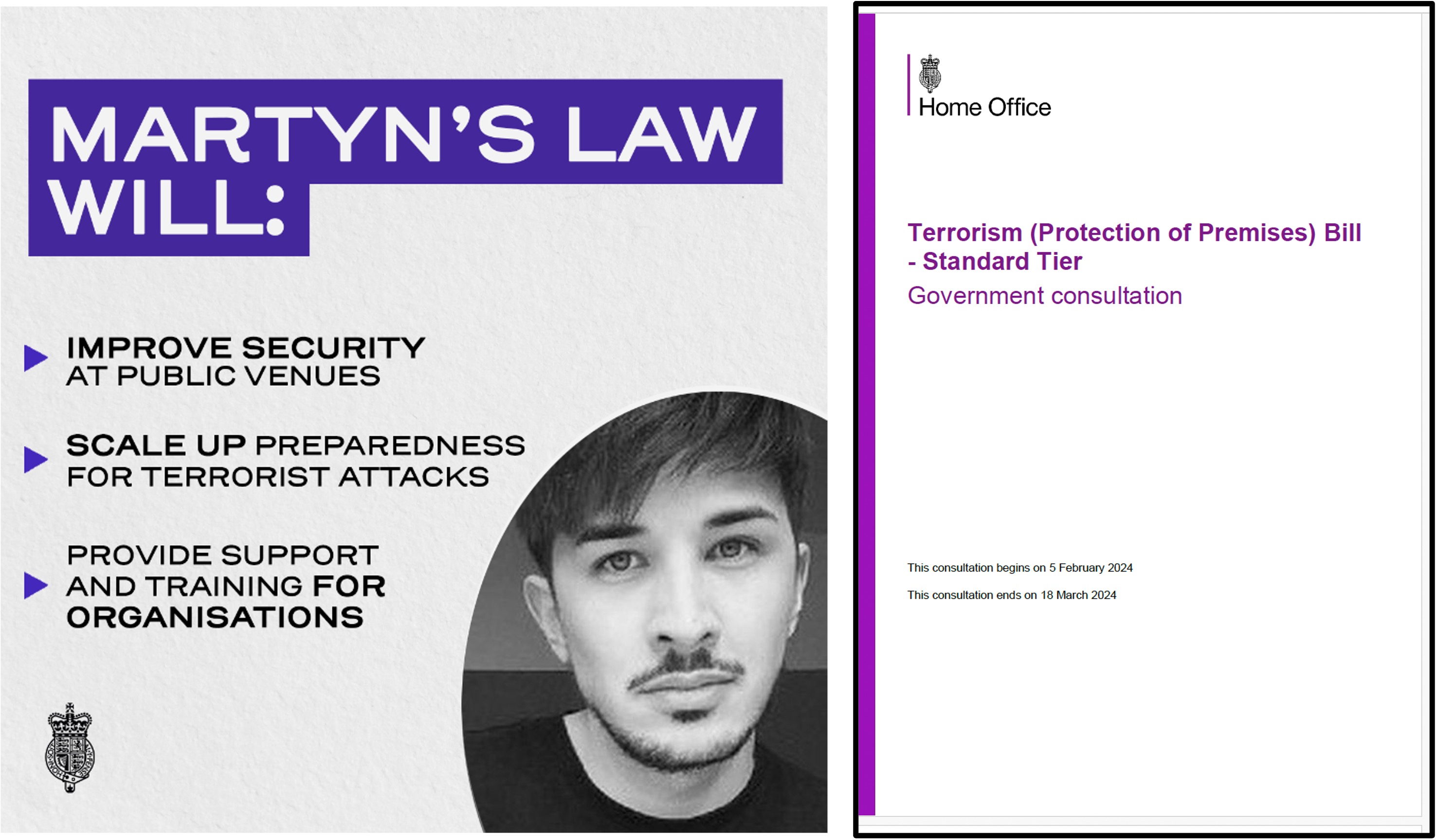

Such is the case with what’s become known as ‘Martyn’s law’, or to give it its official title: the Terrorism (Protection of Premises) Bill. Martyn Hett was one of the victims of the terror attack at the Manchester arena in 2017, and his mother has spearheaded a tireless campaign both inside and outside Parliament. There has been a welter of engagement and consultation and in May 2023 a draft Bill was published. Changes have been made to the original proposals and the current consultation, focused on the Bill provisions in respect of smaller premises (those accommodating 100-799 people) closes on 18th March 2024.

Few people dispute the core objective – to enhance public safety by ensuring there is better preparedness for, and protection from, terrorist attacks. The debate has mostly been about the ‘proportionality’ of the proposals. It’s a difficult judgement to make and so varied are the different circumstances of cinemas, shops, nightclubs, churches and village halls that many have been exercised as to whether the burden imposed by the new requirements will be out of proportion with the element of risk. As a result of earlier rounds of engagement, the requirements for smaller venues have been reduced – though many argue they are still far too onerous.

As individuals and organisations finish submitting their consultation responses – with a large number expected, each one is probably weighing up for themselves – that equation between the risk of something dreadful happening and the inconvenience of the proposed precautions. To help them the consultation paper says that the threat of terrorism is ‘enduring and evolving’. I’m not sure how much this helps.

Fortunately, there is excellent research and the promise of more. I have recently been talking to the Lloyds Register Foundation (LRF) which conducts a World Risk Poll. This is an amazing but little-publicised resource. In 2021, it conducted 125,000 interviews in 121 countries to gather citizen views on all kinds of risks ranging from road crashes, severe weather, climate change and disaster resilience, to work-related harm, violence and harassment at work, and use of personal data. As the Poll findings reveal, there are subjects upon which the public perception of risk is dramatically different from the actual risk. And this varies from country to country and from time to time.

On some occasions, the public’s perception of risk is exaggerated. In the UK we have become accustomed to the public opinion that crime is increasing when it is in fact falling. On health, there has been a different pattern where the public’s perception of the risks attached to obesity significantly underestimates the true risks. In short, the bigger the gap between risk perception and reality – either way – the greater the likelihood of policy mistakes.

One can think of many consultations where stakeholders’ fears have dissuaded Governments at all levels from going ahead with various proposals. Think of NHS reconfigurations. When there were proposals to centralise an Accident and Emergency unit in Huddersfield, objectors from Halifax were told that “147 people will die in the ambulance on the M62 every year.” It matters not whether the calculation is right or wrong. It just illustrates the power to influence opinions and this, in turn can shape policy decisions. Decision-makers in this case were rightly troubled by the extent of public opposition.

The worry is that in the age of AI and deliberate disinformation, communities can be manipulated through aggressive promotion of controversial messages. To be topical, there is huge concern about the trend towards stoking up fears of racial or ethnic hatred; the war in Gaza makes some people in both the Jewish and Muslim communities fear for their safety. Had you asked them to rate the degree of personal risk to themselves two years ago, and then asked them again today, the results might be very different.

In the best public consultations, there is a genuine attempt to explain the nature and extent of the risk in a fair-minded way. It is not always easy. Consider the row in London over Sadiq Khan’s Ultra-low-emissions zone (ULEZ) in 2022-2023. The consultation tried to spell out the health risks of poor air quality, but opponents were not convinced and argued that the data was wrong. When Scotland consulted on its policy on fracking some years ago, the carefully-worded text in the consultation document was ‘trumped’ by a Minister going on television and expressing his view that the risks were much higher than previously thought– and therefore unacceptable.

Public policy is highly susceptible to ever-changing perceptions, and much of the work of pollsters and social researchers is to calibrate the views of different cohorts. What we lack is a better understanding of the true risks we all run. That is why LRF’s work in highlighting the dynamics of risk management is important. At country, region or even global levels it should stimulate public bodies – not just in democracies, but everywhere – to move some issues further up the political agenda. Or maybe de-prioritise others where public education could correct artificially high fears and anxieties.

For Martyn’s law, I suspect there will emerge a classic British consensus, probably tinkering further with the capacity thresholds and the likely thrust of Guidelines that will cover hundreds of thousands of volunteers as well as paid staff for larger venues. The good news is that participating in the consultation will prompt many people to think seriously about the trade-offs and to re-examine their assumptions about the safety of our communities.

Without an effective process of dialogue there always remains the possibility that Parliaments will enact laws that either over-react, or maybe fail to address real problems. In both cases public trust in our democratic institutions can suffer. That is the case for seeking a better alignment of perception and reality.

Rhion H Jones LL.B

See Rhion's Speeches etc - click here

For More like this - free of charge: now click here

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.